“My palate tends more toward a lighter, more acid driven style of wine,” explains owner and winemaker Kelsey Albro Itämeri. This style is driven by both when she picks fruit and how she decides to do so.

“When I make picking decisions, I'm looking honestly for a balance between finished alcohol and acidity,” Itämeri says. “I haven't become too wrapped up in tasting for phenolics. Perhaps people think that I'm a wild child.”

Founded in 2019, itä is located in one of the winery incubator buildings in the airport region of Walla Walla, opening its doors is 2020. The winery name has multiple meanings. It’s a shortened version of Itämeri’s name, translates to “east” in Finnish, and is a reference to a diminutive modifier in Spanish.

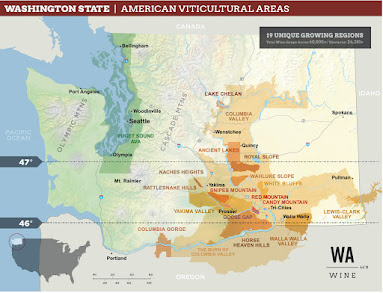

In addition to picking decisions, itä’s wine style is also driven by its fruit sources, which currently come from two sites, Les Collines Vineyard and Breezy Slope. Both are nestled in the foothills of the Blue Mountains, near where Itämeri’s parents own property. Itämeri currently has test plantings on that property, with the goal of eventually having the wines be from estate fruit.

“I just really wanted to explore the terroir, the conditions, and the varieties that can really thrive in this little, tiny section of the Walla Walla Valley,” Itämeri says. She believes Les Collines is well-suited to her style.

“You don't have to be scared to pick so early because you're going to have a really beautiful expression of phenolics, even on the early side,” Itämeri says. In addition to the itä wines being markedly lower in alcohol and having brighter acidity than most currently coming out of Washington, they also see next to no new oak.

“I can't afford new oak!” Itämeri says laughing. “I don't like the way it tastes. Why would I make that wine?”

Thus far the itä offerings have included two different styles of Semillon, a Syrah, a Merlot, a promising Pinot Noir, and a rosé of Primitivo. The Merlot in particular is a revelation, distinct from anything I have seen come out of Washington to date.

“When I'm thinking about what I want the finished wine to be, I think about when are people going to drink it and where are they going to be and how will it make them feel?” Itämeri says. “When I think about the [Merlot] that I want to make, I think about coming home after a bad day, and this is the one you want – the wine that’s going to love you back.”

Though Washington remains largely dominated by fuller bodied red wines, Itämeri and others have shown lighter bodied styles can be made in Washington and made at high quality. They’ve also shown there is more than enough room for stylistic variation in the state.

“You kind of have to just stick to your guns a little bit and be like, ‘This is how I want to win’ and play the game appropriately,” Itämeri says.

itä 2019 Les Collines Vineyard Merlot Walla Walla Valley $45 93 points

This vineyard in the foothills of the Blue Mountains has largely established its reputation on Syrah, but this wine is an announcement that, in the right hands, it can make stellar Merlot in a distinctive style. The aromas pop, with notes of dark raspberry, plum and generous amounts of fresh herbs. There’s a freshness and vitality to the flavors that completely captivate, with vibrant acidity behind it all. It has extended hang time on the finish. Put it on the dinner table to see it at its best. It’s a swoonworthy statement wine for this producer and vineyard. Editor’s Choice

itä 2019 Les Collines Syrah Walla Walla Valley $45 91 points

Les Collines is situated in the foothills of the Blue Mountains and has proven itself to be a special spot for Syrah. Here, this young producer gives a compelling interpretation of this site. The aromas offer achingly pure notes of boysenberry, violet and herbs. The palate shows a lovely sense of elegance and freshness to the bountiful fruit flavors that are light on their feet. A long, lingering finish caps it off. For those looking for pure, unadorned, restrained expression of Les Collines, look no further. This wine flat out delivers. Editor’s Choice

itä 2019 1 of 2 Les Collines Vineyard Sémillon Walla Walla Valley $25 90 points

Fermented and aged in stainless steel, aromas of fig, talc and lemon are followed by focused, sleek flavors and tart, lemony acidity. It’s a wonderfully acid driven offering of this variety. Editor’s Choice

itä 2019 2 of 2 Les Collines Vineyard Sémillon Walla Walla Valley $25 90 points

Fermented and aged in neutral oak, the aromas are light initially, with notes of wet rock, fig and spice. The palate brings a sense of creamy texture yet remains sleek, with lemony acidity stitching it together. It’s as much about feel as flavor, with acid in the driver’s seat. Editor’s Choice

itä 2019 Breezy Slope Vineyard Pinot Noir Walla Walla Valley $45 88 points

Pinot Noir is a relative rarity in the Columbia Valley, with most of what’s planted used for sparkling wines; Pinots from Walla Walla are that much more unusual. It’s light in color and cloudy, offering aromas bursting with notes of strawberry, forest floor, rhubarb and whole tangerine, with the variety immediately identifiable. The palate is light and juicy. It doesn’t entirely stand up on its own but will do well at the dinner table. Pair it with salmon salad with fresh berries and a basil vinaigrette.